|

|

OUR MANAGEMENT PHILOSOPHY

The Kiko goat, as it was originally conceived in New Zealand, was more than a breed, it was a management philosophy. A combination of low-input methods and rigorous culling was the key to creation of these superior animals.

However, without a continuation of the New Zealand approach, the Kiko can eventually lose its "edge." Some breeders provide high quality feed and intensive management to produce well-fed, impressive looking goats that command high prices, but may lack the toughness of the original Kiko. By contrast, we intentionally stress our goats with terrain, weather, parasites and feed limitation, to the point of reproductive failure, or beyond.

We use environmental stress to increase selection pressure and reveal genetic differences that remain hidden under "better" management. Research has shown that for some traits, such as parasite tolerance, much faster genetic progress can be made under higher than normal levels of challenge.

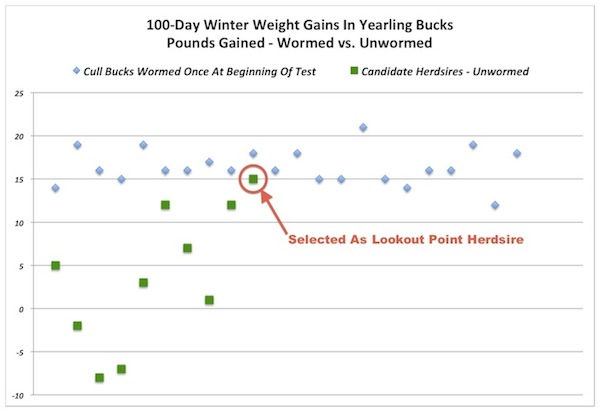

The below graph demonstrates the way that management inputs can mask genetic differences. During a recent 100-day wintertime test, cull bucks that received de-wormer performed uniformly well; almost all gained between 14 and 19 pounds. On the other hand, the performance of candidate herdsires that were not wormed fell across a much larger range, from a loss of 8 pounds to a gain of 15 pounds. If these candidate herdsires had been wormed, there would be no way to determine which buck had superior parasite tolerance.

Our does

are expected to kid at 2 years of age and rear twins to weaning at each kidding, on native vegetation, with no management inputs beyond free-choice mineral and predator control.

We make a point not to "flush" does with better feed prior to breeding, because this reveals propensity for singling - one of the worst traits a doe can have. We also score for udder and for demonstrated maternal characteristics. We do no foot trimming, no worming and no vaccinations. No assistance is given at any birth. The only shelters provided

are trees. Goats that cannot produce under our management are removed from the herd.

While some goats do fail on our farm, there are others that thrive despite the adversity and it is from these that we draw our replacement genetics. The harsh conditions reveal "winners" and "losers" in the classic bell-shaped curve. If we did not stress the goats, these differences would be masked, slowing our breeding program.

It should be understood that our methods are undertaken for the purpose of making faster genetic progress. They are not conducive to the highest outputs possible; our goats do not look or perform their best, while on our farm. Our methods result in severe collateral production losses - such as underweight slaughter animals, fewer kids born, and deaths of both kids and does - that would be unacceptable to commercial producers. Our methods are aimed at developing and producing breeding stock that are better adapted to survive and thrive on unimproved pasture with minimal inputs, particularly in our region. We do not believe it is the best way to get the most production in kids or weight gain - the cornerstones of a successful meat goat operation - and we do not recommend that production farms attempt to raise goats for slaughter under these conditions. Anyone who owns goats, or any livestock for that matter, must set their own goals and priorities.

|